A timeline of the Bay-Delta Conservation Plan

What’s the Bay-Delta?

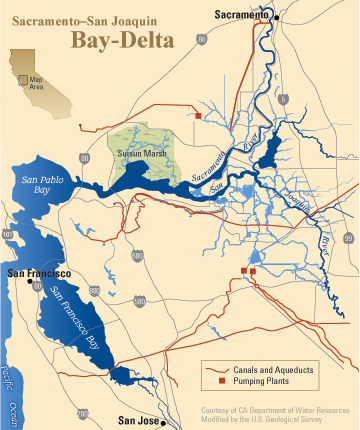

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and the San Francisco Bay comprise the Bay-Delta watershed. The Delta is fed by winter rains and runoff from the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades. The Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers meet and drain into the San Francisco Bay. Interestingly, the Delta is actually an inverted delta, meaning that river channels converge in the downstream direction.

The Bay-Delta is the nexus of California’s water supply, providing drinking water to some 27 million residents (around 75% of the state’s population) and irrigation to 4 million acres of farmland. It’s a crucial migratory zone for birds and fish such as the Chinook salmon.

From the USGS.

The Bay-Delta is threatened by a fundamental tradeoff between its reliability as a water supply and the health of its ecosystem. Delta outflow is at the heart of this issue. The California State Water Project and the Central Valley Project export water from the southern Delta to farms and urban centers. This water diversion threatens fish migration routes, decreases freshwater supply for communities living on the Delta, and induces toxic algal blooms. California has long struggled to push legislation that strikes the right balance between environmentalism and economic interests. The issue of Bay-Delta restoration has become a subject of intense controversy in public spheres, from environmentalist communities to the print media.

A California newspaper contests its sister.

Who’s done what?

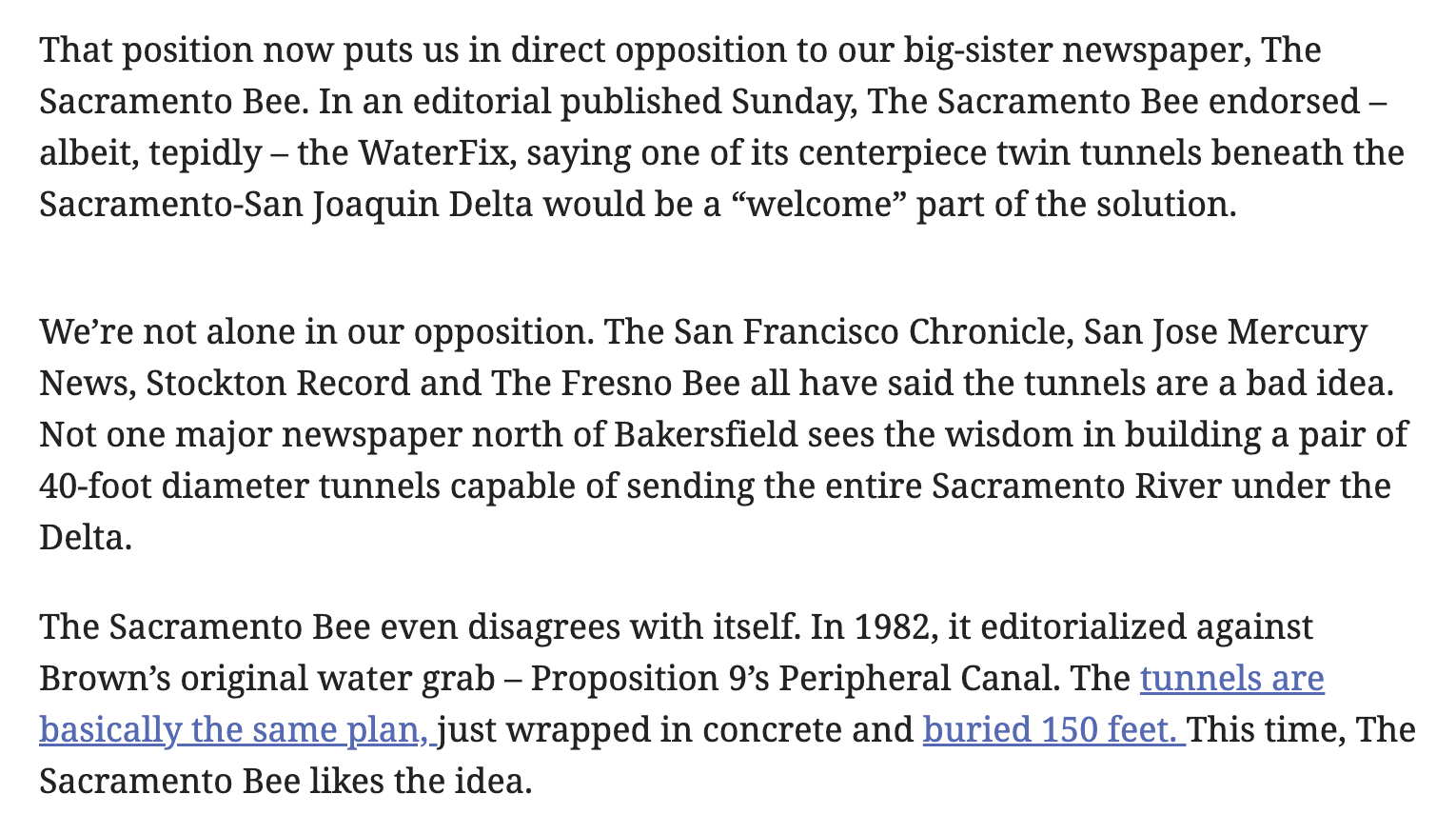

In 1980 state lawmakers approved the construction of a peripheral canal around the Delta to move water from Northern California to Central and Southern California, with the intent of reducing unnatural flows from pumping that confuse anadromous fish. It took days for farmers in the Delta to organize a referendum campaign. The Peripheral Canal was ultimately vetoed in 1982 with unanimous support from farmers and environmentalists.

The Schwarzenegger administration started work on a followup Bay-Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) in 2006 focused on “co-equal goals” of protecting the Delta ecosystem and establishing a reliable water supply. It suggested that over 100,000 acres of habitat would be restored over a 50-year time period. In an update to the plan in 2009, Jerry Brown proposed the addition of two 30-mile twin tunnels that would divert Sacramento River water underneath the Delta via gravity and replace existing pumping systems for a total cost of $25 billion. These tunnels were largely an uninnovative revival of the old 20th century peripheral canal plan.

The BDCP sparked heated debate. Concerns arose over the millions of dollars in economic activity that would be lost by the conversion of farmland into wetlands. Environmentalists said supply could be managed by water conservation efforts. They were more concerned by the reduced flow through the Delta since it would allow salt water from the Bay to creep upstream, arguing that the BDCP failed to describe a specific recovery plan for endangered species. The delta smelt in particular was emblematic of a tension between farmers and conservationists, becoming critically endangered as a result of Delta degradation and representing a threat to farmers with crops on the line.

Environmental concerns aside, the BDCP tunnel costs were high and the project financial plan was obscure. Residents in Stanislaus, Merced and San Joaquin counties worried that their dams and turbines would be rendered useless by river rerouting necessities. On the other hand, proponents believed the project would address risks of levee failure. Some noted that time was running out, species were on the brink of extinction, and complete abandonment of the plan would be dangerous.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would not issue permits for the BDCP in light of its lack of scientific rigor. As a result, Brown drastically scaled down the BDCP in 2015, rebranding it as the Water Fix and Eco Restore project. Eco Restore reduced promised acres for restoration to 30,000 over 5 years, lowering costs from the $8 billion previously required to $300 million. Brown doubled down on the twin tunnels aspect of the BDCP in Water Fix, much to public aggravation.

Delta smelt migrate upstream in the winter for spawning. Meme from Restore the Delta.

2019 saw further downsizing of the conservation effort by the Newsom administration to purportedly save another $5 billion. The Department of Water Resources (DWR) withdrew proposed permits for Water Fix and began preparations for a smaller, single tunnel. The NRDC, a vocal opponent of the Delta twin tunnels, expressed a willingness to consider the new so-called Delta Conveyance Project. After a few months, however, the administration stated a preliminary cost estimate of $15 billion, barely a save on Water Fix. The plan remains highly controversial. Currently the DWR is scoping out environmental impact, engaging with the public, and planning in advance for key regulatory processes. And that brings us to our current moment in 2022.

So…

California has some serious water problems. Legislators have tried for decades to get a serious restoration project underway, but conflicting interests have plans continuously scrapped and thousands of pages of documents flushed down the drain. Proposed new plans are all essentially variants of the same problematic piping solution. In the meantime, the Bay-Delta watershed continues to rapidly deteriorate.